Like laundry, revisions can be a never-ending cycle. Leslie and I make sure to do our laundry weekly and also make sure that our book is as error free as possible.

Like laundry, revisions can be a never-ending cycle. Leslie and I make sure to do our laundry weekly and also make sure that our book is as error free as possible.

While Leslie and I have enjoyed positive reviews and little criticism from our readers, we appreciate a close reading and suggestions like those from an eagle-eyed reader. Marat Grinberg, a professor of Russian and Humanities at Reed College, wrote: I did like [Jewish Luck] quite a bit: it's engaging, smart and really does provide a pretty accurate window into many aspects of Soviet life and the place of Jewishness in it. I do obviously have certain reservations about some aspects of the book, but they're minor - overall I thought it was fantastic.”

Marat eventually emailed us an extensive list of all the corrections—mostly corrections of Russian transliteration of our epigrams. If you want to read those corrections and revise your own copy of Jewish Luck, email us and we’ll send you the list. Even better, buy a new and improved copy!

Aside from learning from Marat’s corrections, his content critique of one word provoked hours of discussion between Leslie and me. We even named our discussion-- “the dialectic of revision.” What was the one word that provoked all this consternation and conversation? The word “propaganda” in the methodology section was the culprit. We used it to describe the 1925 silent film, Jewish Luck. The dialectic of revision between Leslie and me occurred in Sedona, Arizona on the deck of our mom’s place. Our legs propped up on cushy outdoor chairs and shaded by the pines, we dove into discussion while we gazed ahead at the sheer cliffs of Boynton Canyon. Most visitors to Sedona are focused on the red rock, not red history, but the discussion absorbed us. Here are some of the issues we discussed while deciding whether or not to change one word.

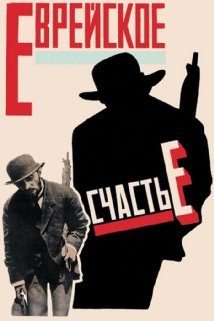

We agreed with Marat’s assessment that [Jewish Luck is] “an amazing piece of cinema.” How did the Jewish writer (Isaak Babel), the Jewish director (Alexsander Granovsky), and the star actor (Solomon Mikhoels) manage to create such a masterpiece and get it past the Soviet censors was our first topic. Leslie and I knew that Lenin’s attitude to film was that “of all the arts, for us the cinema is the most important.” We knew films were subject to Bolshevik censorship in the 1920s. Perhaps Jewish Luck was uncensored because of the timing of its release. Lenin died in 1924, the film was released in April 1925, and Stalin did not consolidate power after 1928. Perhaps the pursuit of Trotsky was absorbing all the Soviet government’s resources and censorship was lax. What was the policy towards Jewish films? This film is scripted in Yiddish so, clearly, the expected audience was Jewish. Maybe the film’s story line and message weren’t relevant to the Soviet authorities. Perhaps the Soviet regime wanted to show that Soviets would encourage and protect the Jewish minority. After all, in 1934 Stalin created an autonomous Jewish region called Birobidjan in the eastern reaches of the USSR along the Amur River. As is usual in our discussions about the USSR, we ended up talking up the fates of the principals who made Jewish Luck. Isaak Babel—killed by the NKVD in 1940. Aleksander Granovsky—moved to Germany in 1928, Paris in 1933, died suddenly in 1938. Solomon Mikhoels—murder staged to look like an accident in 1948 per Stalin’s orders.

Back to the film and our arguments about the motivations behind the making of the film. I began my arguments with “according to my research,” which led Leslie to dispute the notion that researchers could understand intentions and motivations sufficiently to judge whether or not the film was intended as propaganda. In the end, I conceded Leslie’s point. Research has its limits when probing motives. Somehow we managed to avoid a discussion of the use of montage and whether or not the famous Soviet filmmaker Eisenstein borrowed his innovative technique for Battleship Potemkin (released nine months after Jewish Luck) from Granovsky. We had, by the way, tentatively titled our book Jewish Luck before we discovered the film. When I googled our proposed title to see if another author had already written a book with our provisional title, I discovered the existence of the film. We viewed the film on the internet and later watched the entire film at Macalester College.

We had already spent hours researching and discussing the film before we dove into our discussion in Sedona. One might think we’d tire of the endless debate, but, as always at the conclusion of our long and winding discussions about anything to do with Jewish Luck, we sigh, we appreciate our ability to speak without restraint to each other, and we feel energized by the joy of the dialectic.

Note: We encourage our readers to view the film, Jewish Luck to see what all the discussion is about.

Note from Leslie: The cinematographer who worked on the film, Jewish Luck (1925), also worked on Battleship Potemkin (1925) and many of Sergei Einsenstein's films.