This blog was meant as a primer on “How to Research Your Family Tree.” Hah! That’s not going to happen. I was going to interview my husband which turned out to be a lot more difficult than interviewing Vera or Alla. After chasing him around the house for this interview, and then finally getting him to sit down with me, I was struck by the déjà-vu of this experience. It is identical to asking Harry for a recipe. He is so inventive and spontaneous that it is nearly impossible for him to limit his recipe to a set of directions. Most of the instructions begin with “If you’re in the mood…” or “If you have this on hand…” Heaven forbid, we should ever repeat a procedure in our home twice in the same way.

This blog was meant as a primer on “How to Research Your Family Tree.” Hah! That’s not going to happen. I was going to interview my husband which turned out to be a lot more difficult than interviewing Vera or Alla. After chasing him around the house for this interview, and then finally getting him to sit down with me, I was struck by the déjà-vu of this experience. It is identical to asking Harry for a recipe. He is so inventive and spontaneous that it is nearly impossible for him to limit his recipe to a set of directions. Most of the instructions begin with “If you’re in the mood…” or “If you have this on hand…” Heaven forbid, we should ever repeat a procedure in our home twice in the same way.

So, all I can offer is a set of impressions from watching Harry over these past few months.

1. It helps to be a logistics expert.

There are many websites and each has their own strengths. You can begin with the Mormon site (free) Familysearch.org. Yes, even though it is Mormon it has info on the unbelievers too.

You might go from there to Ancestry.com to see what you can obtain for free. Sometimes there are teasers where they show you data about your relative e.g. a census or draft notice that disappears if you don’t pay for membership. If you’re serious about it, fork over the monthly fee of $20/month and you’ll have access to a lot of interesting documents.

My favorite website is Jewishgen.org for all the information about historical and present Jewish communities in Europe.

2. Your family is not so original.

There are a lot of people with your relatives’ names. Any other data you have such as the same hometown as Chaim Weizman, or the name of the boat that brought them over, or the date of immigration is very useful. If you know the port where they arrived, you may be in luck.

3. Documents are fun and informative.

Check for the website of the port through which your family entered. If you know your relatives came through Ellis Island, you can use Libertyellisfoundation.org. It is a free website, but you need to register. No creepy things will happen to you. You can pay to have a copy of the manifest. The information varies by port and year. Here’s what our grandfather’s manifest contained:

- date of arrival

- city of origin, occupation

- can he read or write?

- name and relative in country of origin

- final destination and who he is joining

- whether he’s an anarchist, polygamist, deformed or crippled.

- Height, color of hair, marks of identification

- accompanying family members

- who paid for the passage

Census information and draft registration information are also interesting. Each census, generally every decade, solicited different information. It is available on-line up to 1940 on Ancestry.com. There are frequent mistakes on documents and I am convinced that many of the officers were color-blind. For example, my grandfather was described as being blue-eyed, not brown-eyed, but based on all the other data we had, we knew it was the same person. Sometimes, they are sex-blind. Children sometimes get written down as the wrong gender

4. If you don’t first succeed, try, try again.

Imagine you’re on a linguistic acid trip and think of all the different ways your relatives might have spelled their names. For example, we found our grandmother who we knew as Rae Thomashefsky on the ship manifest as Rachel Tymoschewsky and her mother’s last name is spelled Tymoschevskaja. Ok, this actually makes sense to me as the first spelling might be more Polish and the second more Russian. If you’re from a city that has gone between the two, there may be variations to your home city and your name that are equally valid.

5. You'll find out you're not related to the famous people your family claimed.

We’re still working on our close relationship with conductor, Michael Tilson Thomas and the great Yiddish actor Boris Thomashefsky. We'll let you know.

6. People reinvent themselves.

6. People reinvent themselves.

It isn’t only the port agents who misspell and change names.

Perhaps I’ve told you the story of when my son was born and I named him Isaac, my Aunt Gertie (originally Etta Golda) said “Why couldn’t you give him a good American name like Irving?”

Here’s the history behind that.

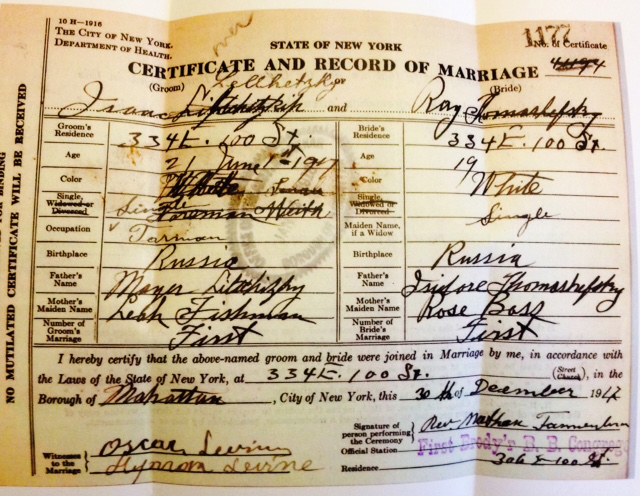

What was my grandfather’s last name before Levine? ---Lelchinsky? Lelchitsky? Lilachitsky and where was he from anyways? On his marriage certificate he writes his name as Isaac Lelchetzky but writes his father’s name as Meyer Lilschizky. His brother and Uncle Hyman have already given up the old last name and are now Levines. Three years later on the 1920 census, he settles on his American name -Irving Isadore Levine – now that’s a real American name according to Aunt Gertie.

7. You’ll learn a lot about geography and history. Borders move and town names change.

But where is Grandpa Irving from? He says he was born in Minsk. Meryll thought she heard Pinsk. Oh, yes somebody mentioned Chaim Weizman’s hometown, which would be Motol. Why does Grandpa list himself as from Poland sometimes and from Russia at others? Was this him trying on fashionable identities? Going on Jewishgen.com helped Harry get a background on families in Eastern Europe as well as a description of towns. Between World War I and II, Motol was in Poland.

8. You’ll be able to contradict family lore.

See #5. All the information you now possess could make you the life or the death of the next family reunion. Your family won’t believe you, but you’ll know you’re right.