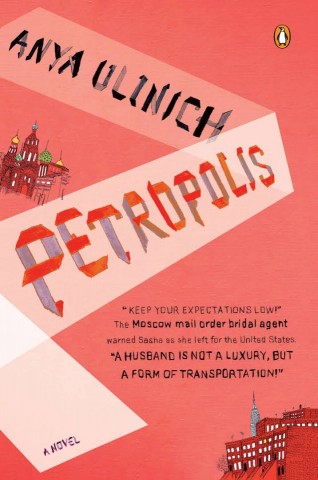

Up from Asbestos 2: A Review of Petropolis by Anya Ulinich

You may already be acquainted with Anya Ulinich, and, like me, think of her as a graphic novelist.After all, I'm sure you all recall my September 14, 2014 book review entitled"What's a Child of Soviet Jewish Immigrants to Do? How about Write a Novel?" which compares the graphic novel Lena Finkle's Magic Barrel by Anya Ulinich to A Replacement Life by Boris Fishman.Spoiler alert, I like Ulinich better.This was actually the first graphic novel I had ever read and I was amazed how many dimensions Ulinich could reveal through the magic of art. Like the film, Annie Hall, we could hear the spoken dialogue, see the characters' expressions and also understand the subtext of what they were saying.

Amazingly, that juxtaposition of text and subtext is done just as well in Anya Ulinich's first book, a non-graphic novel, Petropolis.

Reading this novel, I was embarrassed for Sasha Goldberg, the main character. I could picture her clumsiness, empathize with her shame and poor judgment, and feel the grittiness and dirt of the life around her.What else would one expect from a resident of a Siberian town called Asbestos 2?

Sasha Goldberg is a female schlimazel. She was unlucky to be born in Asbestos 2 in post Soviet Siberia during a time of deprivation before the New Russia became the more prosperous dictatorship it is today.She was unlucky to be dark-skinned and carry a Jewish name, both gifts of her father, half-African and half-Russian, who had already left the country without her. The USSR was extremely racist and her father was a "festival baby," a product of the union of curious Soviet girls and exotic African students who visited the USSR after Khrushchev opened the country, beginning with an International Youth Festival in 1957.

Sasha is barely surviving in a country that has no place for her and with a mother who is constantly putting her on diets.Thank goodness for the communal refrigerator. Her mom's task of creating a cultured child is familiar to us, but far more difficult in Siberia where the purpose seems to be to prove that you are better than your neighbor. It is the one signifier of class in a supposed classless society.After many failures, Sasha does find her talent in art and is accepted to a studio - a run-down room with tyrannical, drunk teachers who limp in and out.

The title Petropolis refers to a 1922 poem by Osip Mandelstam mourning the demise of culture in Petrograd (St. Petersburg) as the Communists seized control of arts and culture. Ulinich eloquently explains the importance of the Intelligentsia in this 2007 interview with Kevin Kinsella*.

"Russian culture was interrupted in the 1920s. After that time, for sixty-odd years, all forms of expression remained tightly regulated. While American culture is a vast collection of subcultures that enjoy different art, music, writing, movies, fashions etc., the Soviet Union had no organic pop culture (with some exceptions such as anecdoti jokes and prison folklore). In this cultural vacuum, certain landmarks of Western civilization (the so-called "high" art, basically, cultural artifacts of a freer world) — classical music, ballet, some types of painting, poetry — attained an exaggerated, cult-like status, becoming a signifier of the 'intelligentsia' class.

Poetry becomes especially powerful in times of oppression — it's compact; it can be memorized, its paper evidence can be discarded, you don't need an orchestra to perform it. Had Russian culture developed organically, Mandelstam would have been as obscure there as he is in the U.S. But in the Soviet Union, he and the other Silver Age poets became kind of folk heroes of samizdat-reading 'intelligentsia' underground.

Okay, so the point is — this 'intelligentsia' designation is very important to Sasha's mother, Lubov Goldberg. In her mind, it distinguishes her from her drunk, fish-off-newspaper-eating neighbors, although her daily life is exactly the same as theirs. She relates to "Petropolis," because her complaint is parallel to Mandelstam's — she is wistful for the pre-revolutionary world of her exiled grandmother, and considers Asbestos 2 a 'post-apocalyptic place.'"

Ulinich is a master of irony. Unlike Petrograd, Asbestos 2 deserves to die according to Ulinich and probably should never have been built.But it is Sasha's civilization."…no wonder Sasha Goldberg is a little surly and Borat-like," stated Ulinich.

When Sasha is sent to the U.S. as a mail-order bride, she brings her bad luck with her. She moves through different types of servitude, from that in her country with limited opportunities, her mother with unlimited expectations, to her husband, Jewish patron and on and on. Her search for family and a livable life is successful due to sheer perseverance and a little help from other marginalized souls.

Ulinich is not a romantic.Sasha's experience in the U.S. is not filled with wonder, but skepticism.The book is worth reading just to shake up our sense of self-satisfaction as Americans and to present what it looks like to a teen from another culture, sensitive to the class differences and material surfeit for what appears to be everyone but herself.

Anya Ulinich, an immigrant from Moscow, came to Arizona with her family at age 17, and like the protagonist of Petropolis, attended art school.She became a novelist, she said, because living in NYC, it provided a more compact workspace than the requirement of a studio area for canvases.She is adaptable.

For me, a novel is worth reading if it takes me into a different world, a different mindset.I want to have characters that make me feel like cheering them on to the finish line, no matter how clumsy and unfortunate they are.I also want to know that the finish line is worth it. By my standards, Ulinich is highly successful in a most original way spicing her story with sharp humor and pathos.

********************

*Kevin Kinsella Interview with Anya Ulinich from www.Maudnewton.com, Sept. 18th 2007. http://maudnewton.com/blog/kevin-kinsella-interviews-anya-ulinich/

Ulinich, Anya. Petropolis. New York: Penguin Books, 2007.